The ongoing Ebola epidemic in West Africa raises valid concerns of a worldwide pandemic in our interconnected world. Travel brings the benefits of trade and sharing of culture, but also the specter of the spread of disease. The Ebola virus was first recognized in Africa in 1976 and prior to the current epidemic had been restricted to isolated outbreaks in remote villages where people had contact with infected primates. That pattern changed when a case occurred in a village near the borders of three countries, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, where travel is frequent. Infections spread rapidly in populated areas, where poverty and poor infrastructure made containment all but impossible. As of early November, there have been 13, 594 reported cases and 5, 410 deaths, numbers which authorities estimate are low due to extreme underreporting.

Because of air travel and infection of foreign aid workers who return home or are evacuated, several Ebola cases have emerged or have been treated outside of Africa. In the United States, a visitor from West Africa died of the disease, while several health care workers, who contracted the virus in Africa or from exposure to the aforementioned visitor, have recovered.

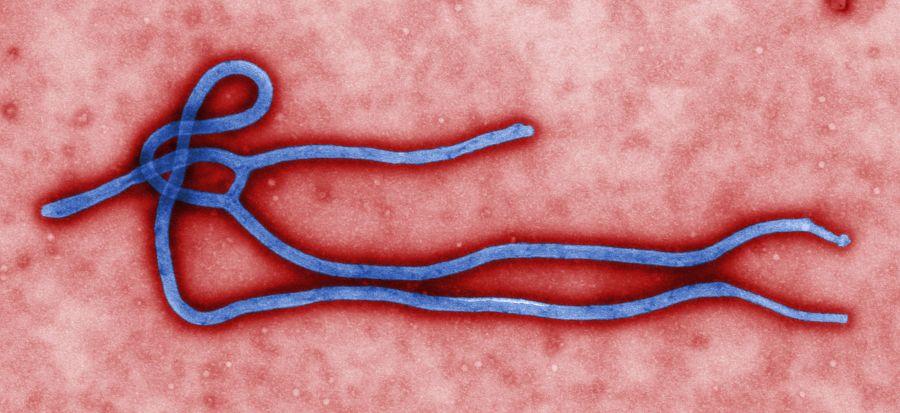

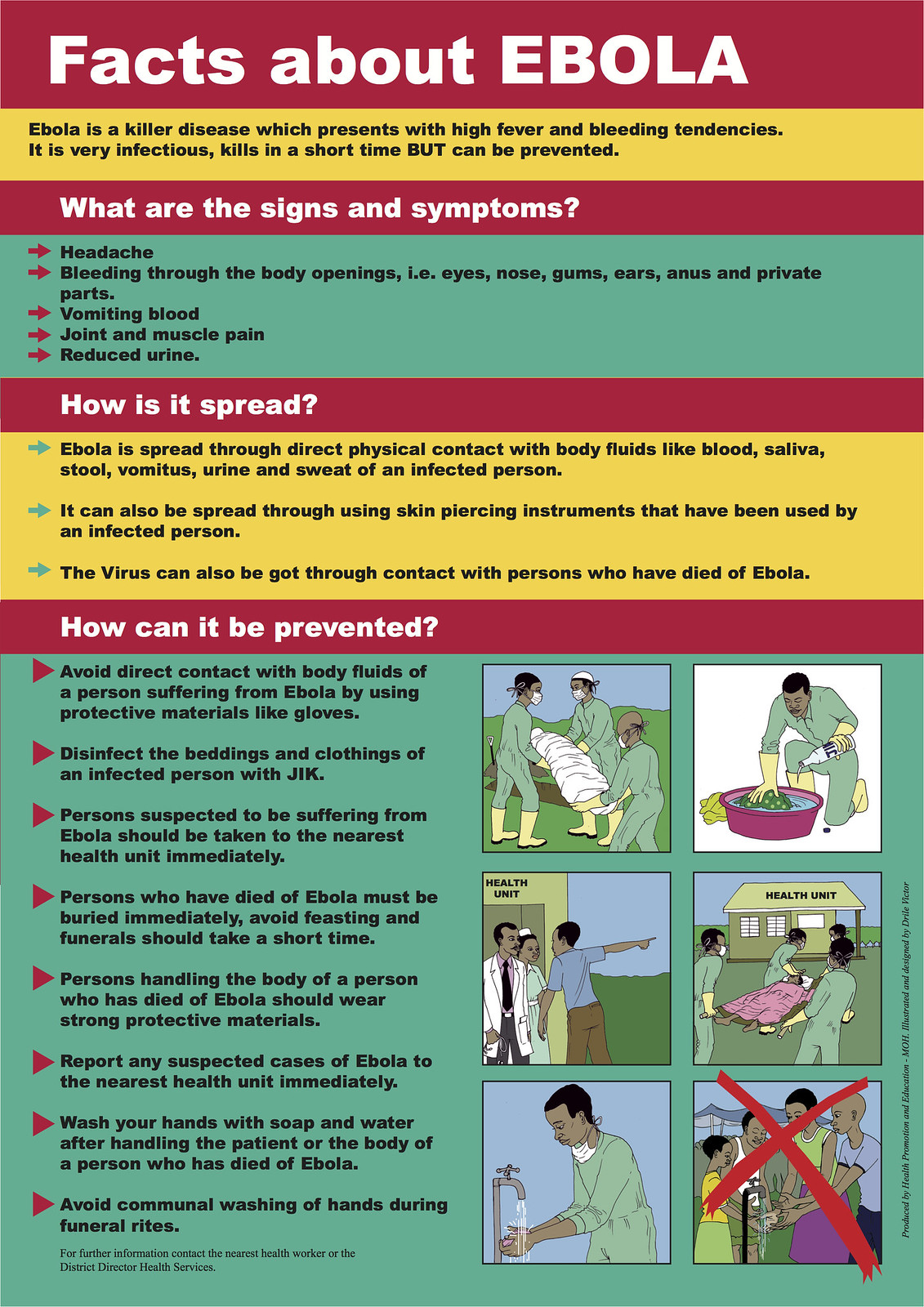

The word Ebola is becoming synonymous with fear and panic. This viral disease has a high mortality rate and treatment is largely experimental at this stage. A vaccine and proven therapies are on the horizon. Although the virus is not transmitted through the air, it is highly infectious, and contact with bodily fluids, such as blood, sweat, saliva, feces, and vomit, is very dangerous.

Authorities in the United States, including the Center for Disease Control, have downplayed the potential for widespread transmission in the United States, citing our robust health care system and ability to trace and monitor those who have had contact with an infected person. Despite such assurances, questions and doubt remain, highlighted by the infection of two nurses who cared for the West African visitor. Although early statements from the CDC advised that any U.S. hospital would have the resources to handle Ebola cases, the accepted position now is that any future patients should be transported to specially equipped regional facilities. In fact, only four hospitals in the U.S. have containment facilities designed for deadly infectious diseases such as Ebola.

Strong sentiments exist among those who believe avoidance strategies are inadequate and those who believe the threat outside of Africa is being overstated. The Governors of New York and New Jersey, Chris Christie and Andrew Cuomo, have implemented an isolation protocol for returning health care workers and travelers known to have had contact with a person having an active Ebola infection. Some other states, such as Illinois, are following suit. The efforts worldwide are focused on stopping the epidemic in West Africa and avoiding epidemic conditions elsewhere. The next few months will be critical in turning the tide of the epidemic. The worst fear is that the a human reservoir will become established for the Ebola virus, as opposed to the limited outbreaks of the past which were initiated by chance encounters between people and infected primates.

Scientists and public health administrators are invested in the race to overcome a new and vicious threat to human health. Other infectious diseases have been conquered in the past century and decades, and there is hope that Ebola will fall as well.